He speaks softly but purposefully, and his eyes dance when he laughs. Sakamoto will turn 64 in January but he wears it well-his sharply cut white hair and tortoiseshell glasses lend elegance to his black zip-up hoodie. It feels cozy and peaceful, and it's where he's been working out of following his recovery from a throat cancer diagnosed in summer 2014. The first half is an office space in which his assistant and colleague quietly work at their desks, and around the corner, there is a jam-packed but methodically organized studio lined with CD-stacked shelves, many keyboards, and a computer. Down a couple of steps and through a gated door is an L-shaped room. I was supposed to meet the eminent Japanese composer in said cafe but thanks to a particularly noisy interview there the day before, I lucked out. On a pretty street across from an arty cafe lies Ryuichi Sakamoto's basement studio office.

That calm feels like a luxury, and, of course, it is. Naturally, I didn’t find the answer.” The piece ends with a shattering climax of crashing metal, chord progressions moving but not harmonizing around each other, and agonizing, unnerving moments of silence.Manhattan's West Village is not like anywhere else in New York-the air has a stillness to it, and there is no sense of urgency, no pressure. So I asked myself what salvation was to me. “I felt there was a new crisis not to be able to save each other. “I was very frustrated with watching the news of starvation in Africa in ’95,” he told CMJ when the recording of the work was released in the U.S. Laurie Anderson and David Sylvian open the piece with their own ruminations an extended passage of bittersweet strings follows. Its four sections terminate with “Salvation,” a wrenching investigation into the meaning of redemption. He also looked ahead with the new symphonic work Untitled 01. Ryuichi Sakamoto & David Sylvian: “Forbidden Colors” (1983)Īs the millennium approached, Sakamoto looked back on his career with 1996, reconfiguring works from his soundtracks for The Sheltering Sky, The Last Emperor, and other projects for a piano trio.

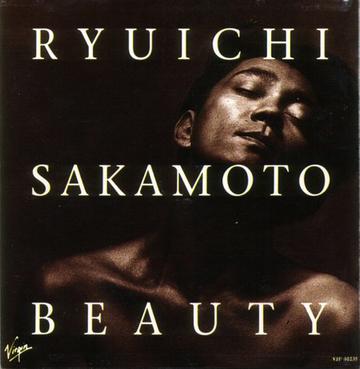

Meanwhile, Sakamoto performed the song in various configurations over the decades, including a beautiful 2013 rendition with an amateur youth orchestra of survivors of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. “Behind the Mask” was a huge hit, with lyrics by the British poet Chris Mosdell, but its critique of alienation turned sour when it was covered in 1987 by celebrities including Eric Clapton and Phil Collins, who both had histories of anti-immigrant bigotry, or by Michael Jackson, who in 1982 turned it into a middling love song that went unreleased for almost 30 years. They were a more ironic Kraftwerk, perhaps, yet the politics rarely traveled well. The trio formed the Yellow Magic Orchestra with the idea, Hosono said, “to take these western ideas of the exotic and subvert them.” It worked like gangbusters: YMO began international superstars, fusing Asian kitsch and innovative electronics. This content can also be viewed on the site it originates from.īy his mid-20s, Sakamoto was already a sought-after session musician in Tokyo when he took up with Haruomi Hosono, previously of the psyche-folk band Happy End and the country-tropical collective Tin Pan Alley, and the glam rocker Yukihiro Takahashi.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)